by Piter Kehoma Boll

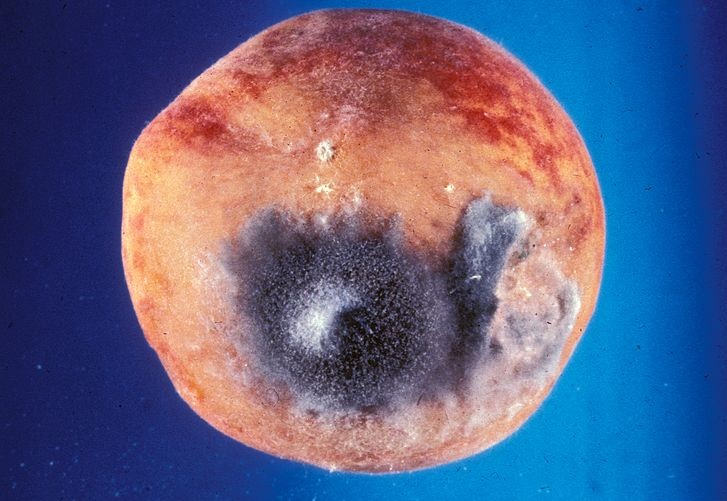

At least once in your life you probably saw a rotting orange with greenish and white mould growing on its peel. This unfortunate condition is caused by the species that I am going to present today.

Known popularly as the green mold or green rot, its scientific name is Penicillium digitatum, being closely related to a similar, but slightly bluer mold that also attacks oranges, the blue mold Penicillium italicum. As a member of the genus Penicillium, this fungus is also related to Penicillium chrysogenum, the main source of penicillin, and to several fungi used to produce cheese such as Camembert (by Penicillium camemberti), Gorgonzola (by Penicillium glaucum) and Roquefort (by Penicillium roqueforti).

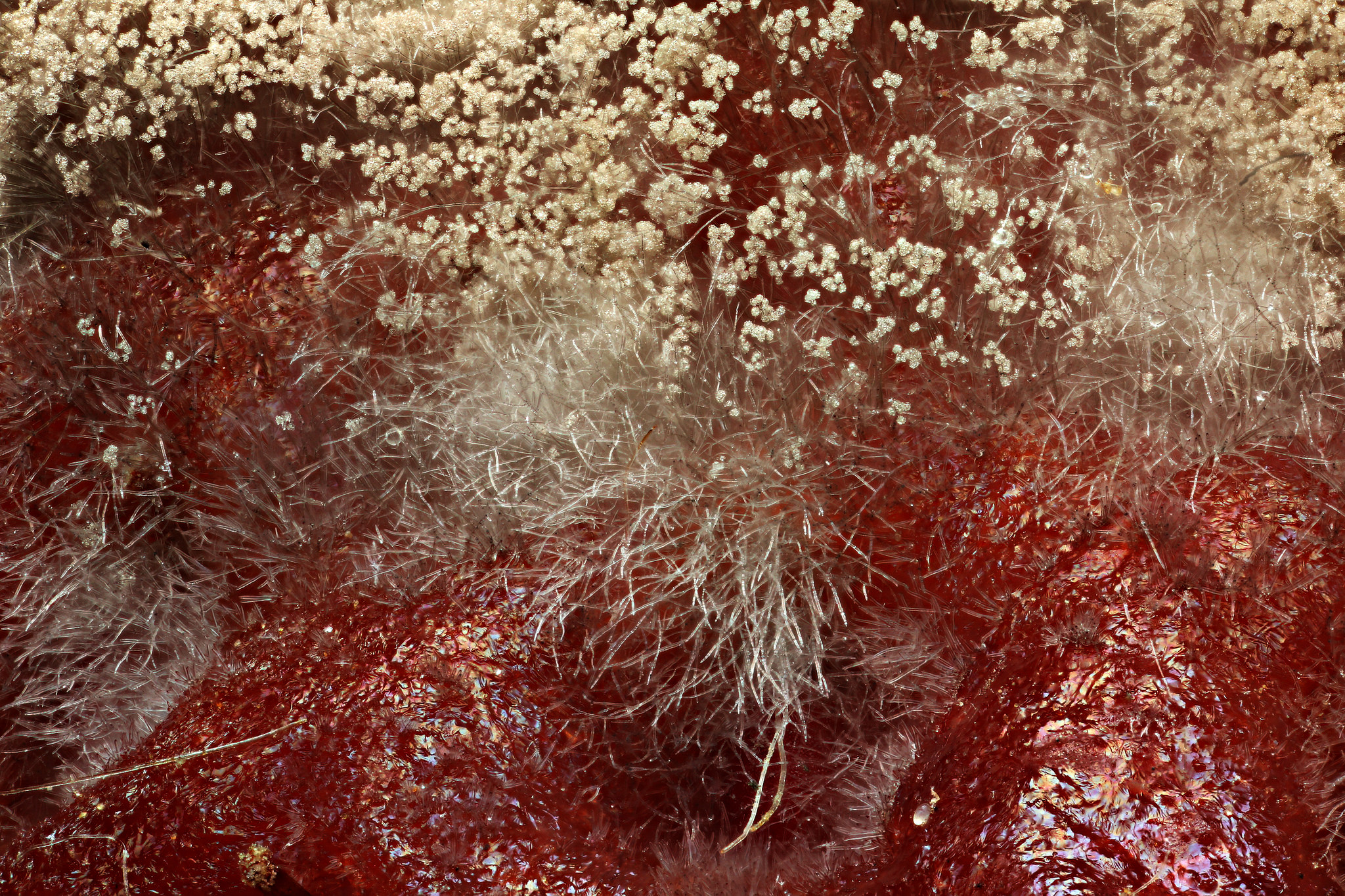

Infecting exclusively fruits of species in the genus Citrus, the green mold grows and feeds on the fruit’s peel, being the main source of post-harvest decay and thus of major economic concern. The optimal temperature for the development of the green mold is 20-25 °C, although it is able to grow in a range of temperatures going from 6 °C to 37 °C. The spores of the green mold are unable to germinate at the surface of the fruits, though, and they need a fissure on the peel to start growing. However, the storage and transportation of the fruits is enough to create small fissures that are rapidly filled by the growing mycelium.

The green mold is known to produce ethylene, an organic gas that is a plant hormone leading to fruit ripening. It is likely that this fungus synthesizes it to induce the ripening of citrus fruits, thus increasing the substrate for its development.

Currently, the main methods used to avoid the spoilage of citrus fruits by P. digitatum include the aplication of fungicides, sometimes in massive amounts. However, as such fungicides can lead to serious environmental and health issues, and sometimes increase the public rejection, there is a demand for the development of less aggressive and more environmentally friendly options.

The genome of the green mold has been recently sequenced, being the second species of Penicillium to be sequenced (after P. chrysogenum), as well as the first main plant pathogenic fungus to have its whole genome analyzed.

– – –

– – –

References:

Chou, T. W., & Yang, S. F. (1973). The biogenesis of ethylene in Penicillium digitatum. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 157(1), 73–82. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(73)90391-3

Marcet-Houben, M., Ballester, A.-R., Fuente, B., Harries, E., Marcos, J. F., González-Candelas, L., & Gabaldón, T. (2012) Genome sequence of the necrotrophic fungus Penicillium digitatum, the main postharvest pathogen of citrus. BMC Genomics, 13, 646. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-646

Plaza, P., Usall, J., Teixidó, N., & Viñas, I. (2003) Effect of water activity and temperature on germination and growth of Penicillium digitatum, P. italicum and Geotrichum candidum. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 94(4), 549–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01909.x

– – –

* This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

** This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.