by Rafael Silva do Nascimento

Talking and exuberant-colored birds always exerted a strong fascination over human beings, and with me it couldn’t be different. Besides, the curiosity that something rare or lost arouses is an important factor to define a theme of interest to someone. Those two combined factors are the foundation that sustains a great interest on my part in extinct species of psittacids, mainly in those ones with little evidence of their doubtful existence.

Talking and exuberant-colored birds always exerted a strong fascination over human beings, and with me it couldn’t be different. Besides, the curiosity that something rare or lost arouses is an important factor to define a theme of interest to someone. Those two combined factors are the foundation that sustains a great interest on my part in extinct species of psittacids, mainly in those ones with little evidence of their doubtful existence.

Several psittacid species inhabitant of island paradises were extinct in the last centuries mainly due to hunting for food, trade to become pets and habitat loss. In this post I’ll deal with a specific species that’s said to have inhabited the Dominica Island, in the Lesser Antilles (Caribbean).

Dominica was firstly inhabited by the Caribbean Indians and later colonized by French and English. Hunting by the Indians is usually sustainable, not representing a great threat for the species.

The colonization by the Europeans, however, has been proved devastating, a common scenario not only in those islands, but also in several other points of the planet.

A forest in Dominica. Photo by Dirk.heldmaier, from Wikipedia.

The Dominican Green-and-Yellow Macaw (also known as Atwood’s Macaw or simply Dominican Macaw), Ara atwoodi, is known only from the report of Thomas Atwood. In his work “The history of the island of Dominica. : Containing a description of its situation, extent, climate, mountains, rivers, natural productions, &c. &c. Together with an account of the civil government, trade, laws, customs, and manners, of the different inhabitants of that island. Its conquest by the French, and restoration to the British dominions” from 1791, Atwood describes the local fauna, whose elements can be associated to the species currently known to the region, with the exception of a kind of psittacid no more found there and that differs from the other ones known in the island (Amazona arausiaca and A. imperialis, which Atwood probably considered a single species in his description) or anywhere else on the planet. The following is the excerpt, adapted to the modern English:

‘’The macaw is of the parrot kind, but larger than the common parrot, and makes a more disagreeable, harsh noise. They are in great plenty, as are also parrots in this island; have both of them a delightful green and yellow plumage, with a scarlet-colored fleshy substance from the ears to the root of the bill, of which color is likewise the chief feathers of their wings and tails. They breed on the tops of the highest trees, where they feed on the berries in great numbers together; and are easily discovered by their loud chattering noise, which at a distance resembles human voices. The macaws cannot be taught to articulate words; but the parrots of this country may, by taking pains with them when caught young. The flesh of both is eat, but being very very fat, it wastes in roasting, and eats dry and insipid; for which reason, they are chiefly used to make soup of, which is accounted very nutritive.’’

Atwood's Description in ''The History of the Island of Dominica'', 1791.

It’s believed that it became extinct by the end of the 18th century or beginning of the 19th century. As there are no extant species of green and yellow plumage (excluding hybrids induced by humans), Austin Hobart Clark assumed that it belonged to a species not yet known to science, firstly including it in Ara guadeloupensis (which is said to inhabit the neighboring island Guadeloupe). With the discovery of Atwood’s account, it was considered distinct, receiving the status of species in 1908.

Considered a hypothetical species by most authors, Ara atwoodi usually isn’t included in non-specific publications that mention recently extinct macaws, which almost always only mention the Cuban macaw Ara tricolor, for being the only one known from preserved specimens, and subfossil forms like A. autocthones. Joseph Forshaw highlight that’s not even safe to associate the species to the genus Ara, due to the absence of specimens, either stuffed or bones, or even illustrations. The association was made by deduction, based on the term “mackaw” used by Atwood, where Clark notices that “his macaw is a bona fide member of the genus Ara”. That, however, didn’t exclude the possibility of being a similar but separated genus that evolved by isolation in the island.

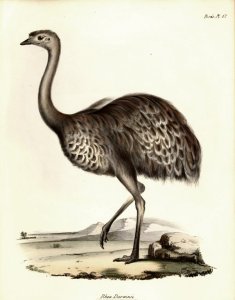

Reconstruction following the picture published in David Day's ''The Doomsday Book of Animals''. Picture by Rafael Silva do Nascimento, 2009.

From the excerpt describing its physical characteristics and based in close species, some reconstructions of how it looked started to appear, though in shyer steps than in other more popular extinct birds. The most widely known is the one present in David Day’s work “The Doomsday Book of Animals” (1981), which depicts a macaw well distinguished from the species whose appearance was known, not having the portion of bare skin on its face, consisting merely of a closed portion, but following the color pattern described by Atwood. Most posterior reconstructions are based on this picture. Other obscure species with a similar history are portrayed, like Ara erythrocephalus from Jamaica, which was also reported having green and yellow feathers, but with a red head. The color as it was described and the observation of extant species suggest a pattern similar to the one found in Ara ararauna and maybe in A. martinicus from the neighbor island Martinica (another hypothetical extinct species), with blue replaced by green. Also reported from Jamaica, but not creditable by most sources, is A. erythrurus, said to be similar to A. ararauna, but with an entirely red tail. Julian Hume in his book “Extinct Birds” to be released in February 2012, which also have Michael Walters as author, portrayed the species according to this idea, however without having the portion of bare skin on the face painted red, but only the forehead of this color. Since I didn’t have access to the work of Walters and Hume, I’m not aware of the reason for such a reconstruction, but considering that the reddish facial portion, usually seen as a distinct feature of A. atwoodi, may be simply excitation as observed in A. ambiguus, A. militaris and A. rubrogenys, this macaw may have been represented in a “calm” situation. Both A. ararauna and A. glaucogularis can show traces of redness on the face, being more evident in the last, so if A. atwoodi was truly a close relative, this feature might be more advanced in this species. A color pattern that recalls the described by Atwood is found in the pet market as in the hybrids Catalina (A. ararauna x A. macao) and Harlequin (A. ararauna x A. chloropterus), where the back is green and the belly varies from shades of yellow to bright orange.

I've made this reconstruction following the theory that A. atwoodi was closely related to A. ararauna. Some elements, such as the black patch below the bill, are highly speculative.

While I see sufficient evidences to declare the existence of a different form of macaw that once inhabited Dominica, its real appearance will remain a mystery until new evidences came to the surface, whether they are lost reports or subfossil bones.

– – –

References:

Atwood, T. 1791: The History of the Island of Dominica. London: Frank Cass and Co.

BirdLife International (2011) Species factsheet: Ara atwoodi. Available on-line in: < www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=30080>. Acess on December 6th, 2011.

Clark, A. H. 1908. The Macaw of Dominica Auk, 25, 309-311

Forshaw, J. M. & Cooper, W. T. 1977: Parrots of the World. T.F.H. Publications, Inc. New Jersey.

Fuller, E. 1987: Extinct Birds. Facts on Files Publications. New York.

Maas, P. H. J. 2007: Dominican Green-and-Yellow Macaw. In: TSEW. The Sixth Extinction Website. Available on-line in: <www.petermaas.nl/extinct/speciesinfo/dominicanmacaw.htm>. Acess on December 6th, 2011.

Many-feathers. Catalina Macaw. Available on-line in: < www.many-feathers.com/Catalina-Macaw.htm>. Acess on December 6th, 2011.

Rothschild, W. 1907: Extinct Birds. Hutchison, London.

Williams, M. I. & Steadman, D. V. 2001: The historic and prehistoric distribution of parrots (Psittacidae) in the West Indies. Pp 175-489 in Biogeography of the West Indies: patterns and perspectives. 2nd ed. (Woods, C. A. & F. E. Sergile, eds.) Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.